Home is what I long for when I'm somewhere else.

The feeling of belonging

“[A place] into which a person is born, where the early socialization experiences take place, which largely shape identity, character, mentality, attitudes and also world views”, quoted Nora Krug the Brockhaus definition of Heimat in her eponymous graphic novel. The author from Germany, later living in New York City, is refurbishing the historical past of her family in it.

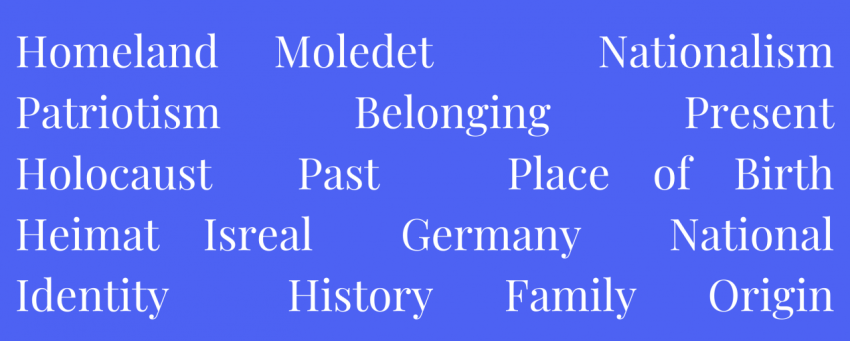

Nora Krug is not the only one, writing about belonging, fear of identity and the ongoing problematic of terminologies such as ‘Heimat’ and ‘Moledet’.

The theme is sensible and emotionally charged. In a country, where antisemitism and racism have led to the biggest mass murder in history, it is the responsibility of each individual to question his or her own political and social behavior. That leads people like Nora – born 1977 in Karlsruhe – to question their whole life and doing research on family history, which often leads to confrontations with one's own NS past. But where is the point to make peace with your home country? Is it okay calling Germany your home and being proud of it at the same moment? Or is it the duty of all of us to criticize the past whenever mentioning that we are born here and also our grandparents have lived here under the NS regime? And how has the Holocaust and WW2 influenced the feeling of belonging for people living in Israel? What do they feel about nationalism?

Having an eye on the current political tendencies, it seems that some people are forgetting about that horrible part of german history. So called ‘concerned citizens’, avowed nazis and right-wing populist groups organise and represent themselves in german society. The right-winged party AfD reaches 20.8 percent in in the current state election of saxony-anhalt, a federal state of germany.

Right-wing groups take concepts like homeland and patroitism as their own and coin them. Are we as a society supposed to take them back and define them in a new, liberal and world-open way? In a survey conducted for this project people were invited to tell about their personal feeling of belonging.

Associated with this feeling were things like family, friends, special people, memories. But also the same language, identification and traditions were mentioned several times. The Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung summed up literature about the “Heimatbegriff” as a “dynamic concept. As a cultural being, man by nature needs a social space, the home – which is why he creates it again and again in his consciousness and through his behavior.” What it means to be forced to leave your home, deny your identity and leave your social place tells Evelyn in her article about the displacement of her Hungarian grandparents during the World War II.

Are we able to re-locate the meaning of belonging independently of origin and ethnicity, beyond intolerance and aggressiveness? Nora Krug gave her belonging a new definition. She researched about her family history, questioned the behaviour of her grandparents during WW2, refurbished her past and seeks application in the present with the help of reflection.

Considering the answers of the survey, not everybody seems to take the german past as commitment for reprocessing in the present. Six of the 36 participents specify that they feel proud about being german – three of them do not feel free to express that. The same people answered the question about how much impact the past has on their present: "Does not influence me" or "It is not possible to talk freely everywhere about personal thoughts about the country. In a certain way, one is simply very restricted, although one does not identify oneself in any way with the past".

One of the answers about the influence of the Holocaust on the national feeling today was:

“Hardly. For me, national feeling arises in the present.”

Well, is it that simple? Living in the present displaces the past and we can live happily ever after? The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung explains the last 70 years after the Holocaust as an Awareness process. The people need to re-locate their feeling of belonging, the definitions of patriotism and nationalism require a clear demarcation. While “Patriotism describes a socio-political behavior in which individual interests are not the guiding principle, (...) but the well-being of all members in a politically constituted community as the epitome of the conditions for being able to live and develop, Nationalist value loyalties demand internal social homogeneity, blind obedience and idealized overvaluation of one's own nation."

The word process includes, that something is still ongoing. We can not feel patriotic, when racism and exclusion are still a thing in the political constituted community. That might be one reason, why for most people that answered the survey,i t is not central to identify with the German nation. The past still has a huge impact on the current feeling:

“It influences me in that it shows where national identity can lead in the worst case and it is our duty as Germans to prevent this from ever happening again.”

Looking 4,000km south-east, the feeling of belonging is different but somewhat shares the german past in a very sad way. ‘Moledet’ in Hebrew literally means place of birth. But very often 'Moledet' means something deeper than that. Someone's 'Moledet' does not mean the place they were born, but the place they belong, or more accurately their people belong. Two men from Israell explained, how they feel about their personal 'Moledet'.

Not all Jews associate Israel as their homeland, as their 'Moledet'. This was the case for a lot of Jews living in Germany up until the rise of the Nazis, or for Jews living in America today, and also for Jews living in Egypt like Guy's father's side of the family, which will be discussed in the next article.